The Mystery of the Normal Distribution in Nature

Laid bare

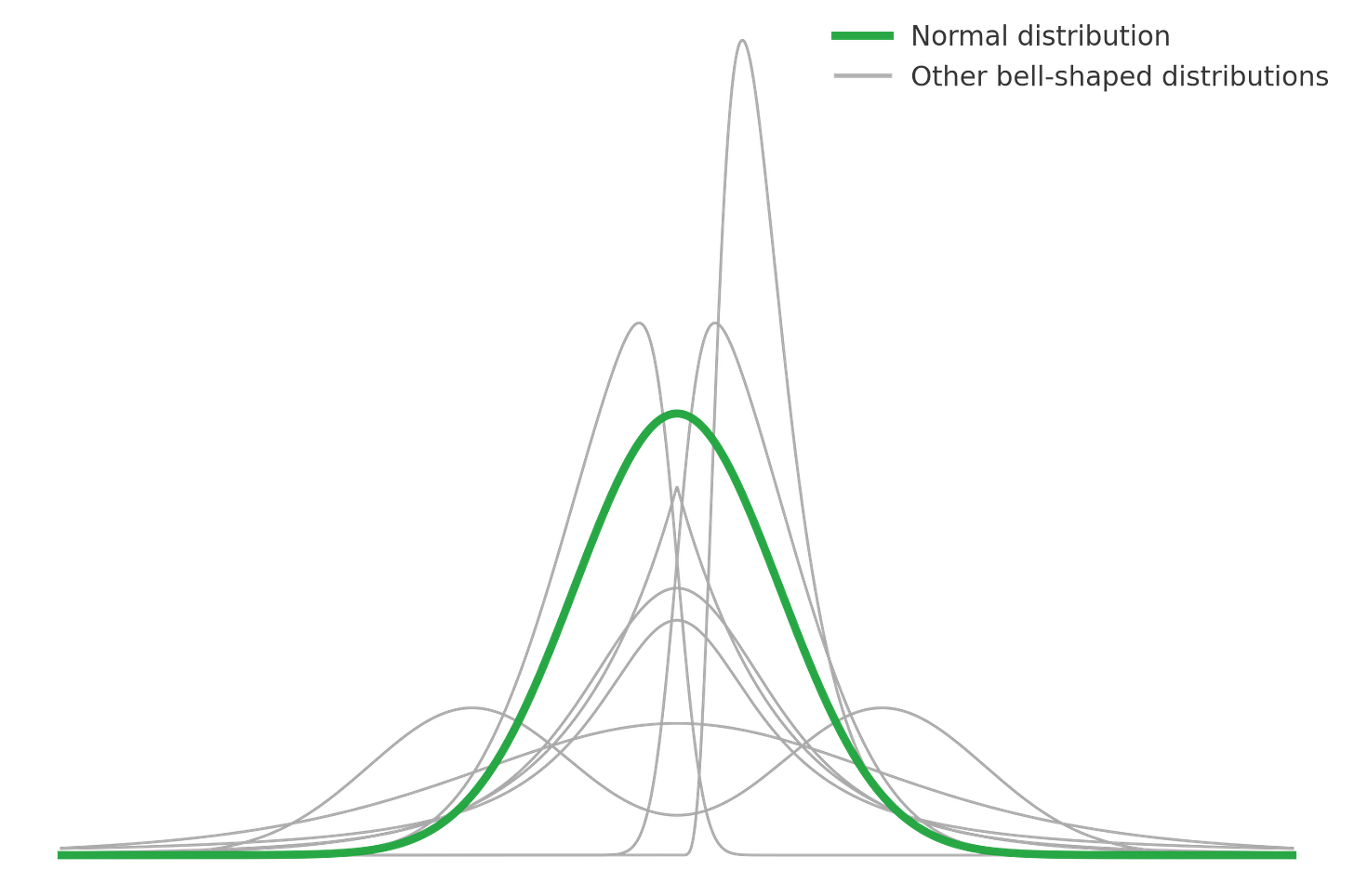

“The normal distribution is the most common distribution in nature.”

I heard this countless times in school…

The bell curve itself makes intuitive sense—there are few very short people, few very tall people and lots in the middle, right? But something deeper bothered me. My teachers were making an extraordinary claim: among infinite possible bell-shaped curves, nature consistently chooses one specific mathematical form.

How could this be?

The answer lies in a remarkable property. When you add up many small components, their sum tends toward a normal distribution. If human height is the sum of many body segments, then height will be approximately normally distributed.

But there’s a catch—it won’t always work. Several conditions must be met:

Components are independent

Each component must have finite variance (the distribution tail decreases sufficiently fast)

No single component can dominate the others in terms of variance (Lindeberg’s condition)

You need enough components

Are these conditions realistic? Do they actually occur in nature?

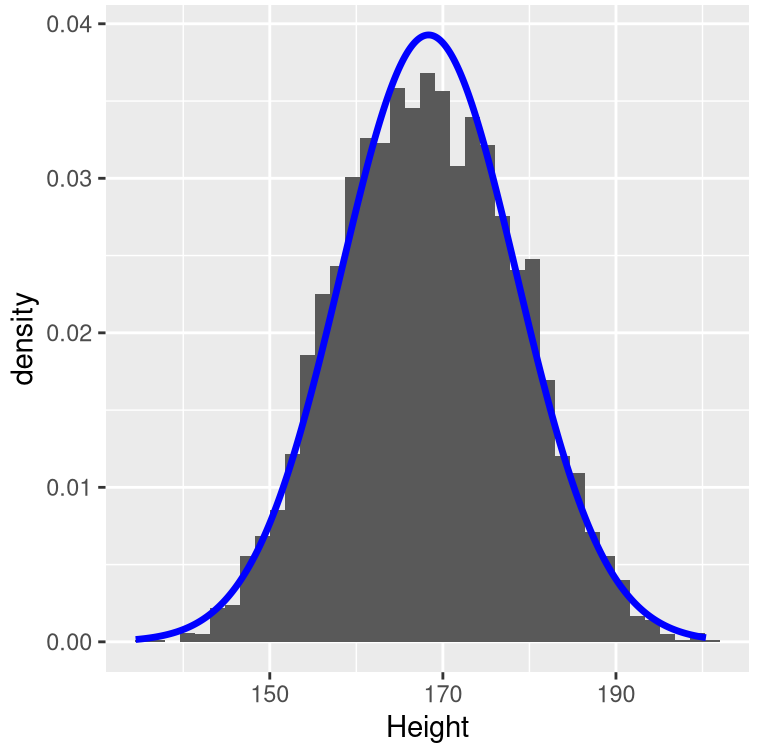

The Human Height Example

Adult height serves as an empirical example of a normally distributed biological trait in textbooks on statistics¹.

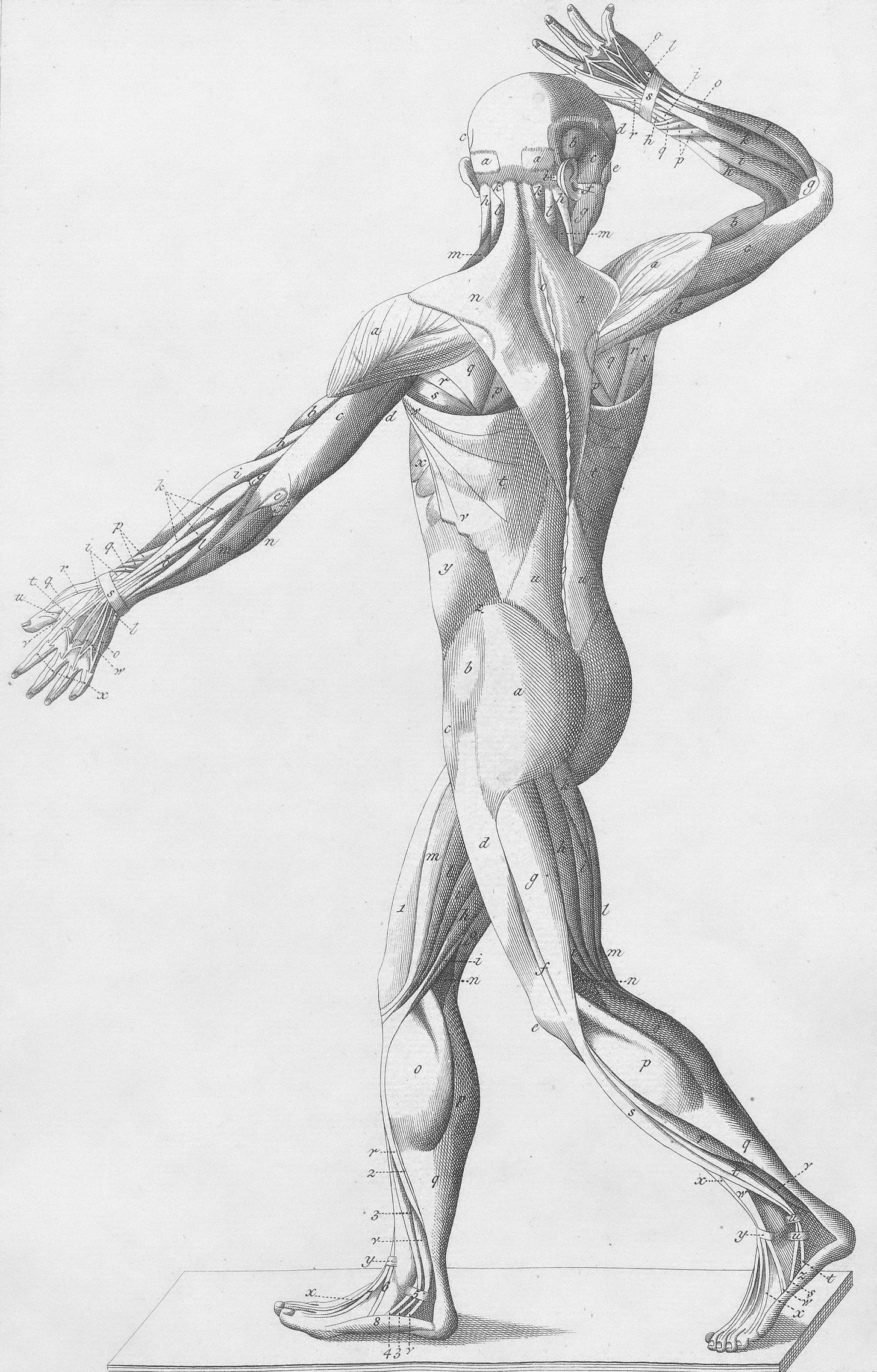

Let’s examine human height more closely. At a basic level, we might divide the body into major segments, say: foot, ankle, calf, knee, thigh, hips, belly, chest, neck, and head height. For these to sum to a normal distribution:

they cannot influence each other

their individual variances must be fairly similar

and with so few components, each would need to be nearly normal itself

The number of components is the key.

Instead of a few major segments, imagine dividing the ankle into all the bones and other tissues that comprise it. Go further—consider parts of these bones, or even smaller, unspecified fragments beyond human nomenclature. Suddenly, we have a large number of micro-components. Now the requirements become much less strict:

still independent

but the component heights can have varied distributions, far from Normal

and more different variances

Yet, their sum will still converge to a normal distribution.

Central Limit Theorem

This remarkable property of the normal distribution has a name: the Central Limit Theorem (CLT).

The requirements described here apply to the Lindeberg-Feller version, but other formulations exist with different conditions. You can often trade one requirement for another—or several others. The more you remove, the fancier the new ones become.

Either way, one of the versions is apparently often satisfied in nature, and that’s why we can observe the Normal distribution so frequently.

P.S.

This post was inspired by reading The Art of Statistics: Learning from Data by David Spiegelhalter. As I mentioned in my previous post, I’m going back to basics. I’m on page 100 of 400 and I’m fascinated. My notebook is full of ideas for future posts. We’ll see how much my upcoming newborn will let me actually write them ;)

¹ Slavskii, S.A., et al. (2021). “The limits of normal approximation for adult height.” European Journal of Human Genetics, 29, 1082–1091. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-021-00836-7